How the hobby remembers 45 years of Mets history

On April 17, 1964, the New York Mets finally had a home to call their own. After spending two years at the Polo Grounds, the Mets began their 45-year stay at Shea Stadium. It may not have been the fanciest stadium around, but it hosted one All-Star game, four World Series, and a fair number of Hall of Famers. Unlike the stadium celebrating its 100th anniversary this year, Shea’s era couldn’t go on forever. In 2008, fans said a final goodbye to the only Mets home many of them had ever known.

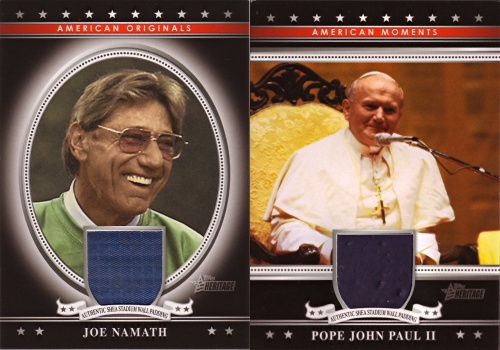

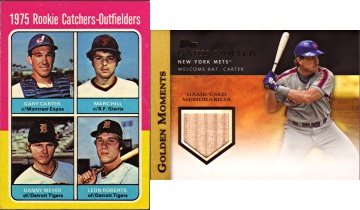

A bittersweet part of any stadium demolition (or sometimes even renovation) is the selloff of anything that can be unbolted or torn off. In the old days, wooden stadium seats would find their way into museums and private collections (and later baseball cards, as seen in this year’s Heritage and Gypsy Queen). Until its demise, Shea had never been cut up and stuck into cards. This changed with 2009 Topps Heritage, which featured Shea Stadium memorabilia in its American Heritage Relics insert set. For the first time ever, fans would be able to buy a tiny piece of their home stadium (if they thought that $100 or more for a plastic seat back was a bit too steep).

The stadium memorabilia of choice in this case was padding from the outfield wall. The big question though would be who to put on the cards with tiny pieces of blue wall embedded in them. Mike Piazza had previously appeared on game-used wall cards, but for other stadiums; this of course made no sense because Piazza was a catcher, but that didn’t really matter for these cards. For Shea though, it wouldn’t do to put the faces of players from other teams alongside the last remnants of the Mets’ former home. So who would make sense?

Lenny Dykstra immediately comes to mind. His crashes into the outfield wall earned him the nickname “Nails” (and probably a bit of brain damage), so how could you go wrong with Lenny on an outfield wall card? Dykstra was flying high as a financial genius at the time, right before filing for bankruptcy and landing in jail on every kind of non-violent felony charge you could imagine (and maybe a few not so non-violent ones). OK, so we dodged a bullet there

How about the 2000 World Series starting outfield of Benny Agbayani, Jay Payton, and Timo Perez? Could there be a more unlikely starting outfield in the World Series? This story would probably play out better if they won that one, but it’s still worth a thought.

You could just go with a big star who played in the outfield at Shea and Willie Mays is about as big as they come. Despite spending only the very end of his career with the Mets, he is still featured on plenty of cards in blue pinstripes.

There’s always Darryl Strawberry, who still holds several team records (at least until David Wright breaks them). Or maybe Carlos Beltran, one of the best Mets from the 2008 team. There are countless stars and fan favorites who could have worked..

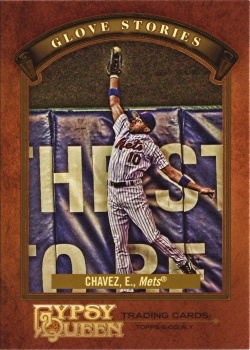

Forget all that, there’s only one Mets player who should be on a card with a piece of Shea Stadium’s outfield wall. The Catch. For most baseball fans, that phrase is associated with Willie Mays. To Mets fans though, The Catch is synonymous with Endy Chavez and his picture-perfect home run-robbing catch in Game 7 of the 2006 NLCS at Shea, right in the middle of an AIG ad that said “The strength to be there.” The Catch was such a significant baseball moment that it was even featured in 1 and 1/3 of a second of Fox’s two hour 25th anniversary special this year. It was just meant to be.

Which is why it never happened. So who would be deemed worthy of this honor? Not Mays or Chavez. Not Dykstra or Strawberry. Not Benny or Timo. Not even Beltran. The winners were Joe Namath, Pope John Paul II, Pope Benedict XVI, President Bill Clinton, and New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg.

Namath actually played at Shea for most of his career, but what the heck do popes and politicians have to do with the outfield wall at Shea? Apparently the criteria for selection ended somewhere around “visited the stadium at least once.” And I guess they couldn’t get the rights to The Beatles. Worse though is that Endy’s catch, while widely covered in photos, went unrecognized in baseball cards. Until now (or a few months ago to be precise).

And we finally get to the point of this piece, the 2012 Topps Gypsy Queen Glove Stories card that commemorates The Catch at long last. It took almost six years, but we finally have a cardboard reminder of one of the best postseason plays in recent history. If only this could have been combined with the Shea outfield wall cards…

Recent Comments